Mary Maker is an actor, a writer, and a refugee education activist working with United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR). She co-founded Elimisha Kakuma to provide access to higher education opportunities for high school graduates living in Kakuma Refugee Camp in Kenya, and is currently pursuing a degree in Theater at St. Olaf College Minnesota.

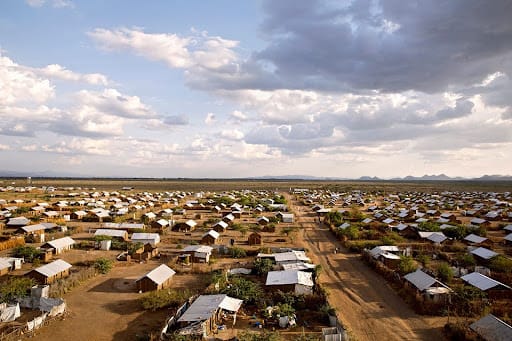

When I first arrived at Kakuma Refugee Camp as a child fleeing war in southern Sudan, it felt like a haven of peace. But my mother saw something different. To her, it was a place where people became numbers, anonymous stories—or worse, untold stories. A never-ending circle of war and conflict.

It wasn’t until I had spent a decade in Kakuma that I began to understand its permanence. I watched as family members were buried, and the rest of us waited, year upon year, hoping to be among the lucky one percent who would be resettled, or to be among the less than 1% who would go on to access higher education.

Leaving a refugee camp isn’t easy

When I was accepted to St. Olaf College in Minnesota, it felt like the world had stopped for me. As if all my problems had ended. After all, this was the dream! Being chosen as one of the few students from a camp of close to 300,000 refugees—almost half the population of Boston—to go to college made me feel like I had beaten the system.

But then I realized that getting a $73,000 per year scholarship was tough, but actually getting to college might be even tougher. I had to sneak out of the camp because the camp manager’s office refused to sign a permit for me to leave. I didn’t know the procedures needed to secure a Convention Travel Document (CTD), a document accepted worldwide since the 1950 Geneva Convention, so I sadly didn’t get one. But I learned that for some of my friends who did secure a CTD, it meant nothing to the person handling their visa interview, who didn’t even know that refugees can travel on non-immigrant visas.

For aspiring students like me, there are countless other barriers like this—trying to collect documents that don't exist; navigating bureaucracies that seem designed to keep us in the camp; finding money to pay for tuition, yes, but also books, flights, buses, and new, weather-appropriate clothing.

Then, when we have accomplished the impossible, we have to say goodbye to family and friends, perhaps for the last time. Few of us leave the camp, but even then the camp never leaves us.

From camp to campus, the struggles continue

Arriving on campus brought even more challenges: signing up for classes, shopping at the Mall of America, going to the supermarket—things that might sound fun or easy were new and overwhelming. Who knew there could be so many types of milk, or cheese, or even water?

At 23, I learned to drive. I discovered that going to office hours is okay, and even encouraged, and that experiencing mental health issues isn’t a sign of being bewitched or mentally unstable. I had to accept that I didn’t have to feel guilty about keeping some of the money I earned for myself rather than sending everything to my family back home. But I still found myself converting nearly every dollar into Kenyan shillings.

Because money was so tight, I missed out on a lot of social life on campus. I know friends, fellow refugees, who had to drop out due to loneliness on campus and the so-called “Black Tax”—a term they use to describe the financial strain of balancing campus jobs and expenses while still supporting family in the refugee camp. The system failed them.

But I managed to graduate. I graduated because I had a support system, a host family to guide me, dedicated teachers and a career center on campus that engaged me.

Taking matters into our own hands

No one should have to fight as much as I did to get where I am. Our hunger to see real change is what drove my team and me to start Elimisha Kakuma; we realized that our students needed both preparation and community support. We realized that's how we win.

Through Elimisha Kakuma, we offer refugee students carefully curated classes that encourage critical thinking and address educational gaps caused by years of conflict. Support had to extend beyond the classroom. Once accepted to college, our students find support from host families and mentorship programs for building resumes, LinkedIn profiles, and other professional skills.

Being a refugee is complex; being a refugee student adds another layer of complexity. As an advocate for access to education, I’ve come to understand that creating access is more than just helping to secure an admissions offer; it means confronting the systems that make it so difficult for people to leave the camp.

Duolingo's access program is a great example of an organization doing more: in addition to giving people free Duolingo English Tests, they have partnered with the UNHCR to provide on-the-ground support for students, helping them to navigate the daunting university applications and admissions processes. But even with Duolingo’s support, many hurdles remain.

Refugees are counting on you

We at Elimisha do our best, but we need more partners. Through their access program, Duolingo is working to ensure that no populations face barriers to education, investing in those that are not able to access testing around the globe. We need everyone to follow their lead. With a supportive community, we can integrate refugees into a network, guide them through the confusion and loneliness of being away from home, and collectively address the barriers they face.

To truly support refugee students, we must go beyond just offering scholarships and admissions; we need to provide these individuals with a home and a community. Every one of us has a role to play. As Maya Angelou puts it, “I am counting on you counting on me.”