📩Welcome to the first installment of Ask Dr. Masha, an advice column for stakeholders in international education!

Hi there! It’s me, Dr. Masha Kostromitina, a Senior Research Communications Manager for the Duolingo English Test. I’m an applied linguist specializing in language assessment, and in this column, I’ll answer your burning questions about English proficiency and assessment!

A lot of people ask me how various language constructs are measured on the DET, and it seems that in particular, the writing construct is on top of everyone’s mind—and this is no surprise, since we know that writing skills are critical for university study.

So, let’s talk more about how the DET approaches writing assessment—forewarning, it is actually pretty revolutionary!—and what this means for institutions evaluating their international applicants.

How do we define the writing construct?

Current research in writing emphasizes that it is not a monolithic skill, but rather a complex set of related abilities that manifest differently depending on context, purpose, and audience (Deane et al., 2008; Mays, 2017).

Because of its complex nature, we conceptualize writing proficiency as a multifaceted construct that integrates both product and process dimensions. These two dimensions are essential for effective written communication both in academic and general contexts.

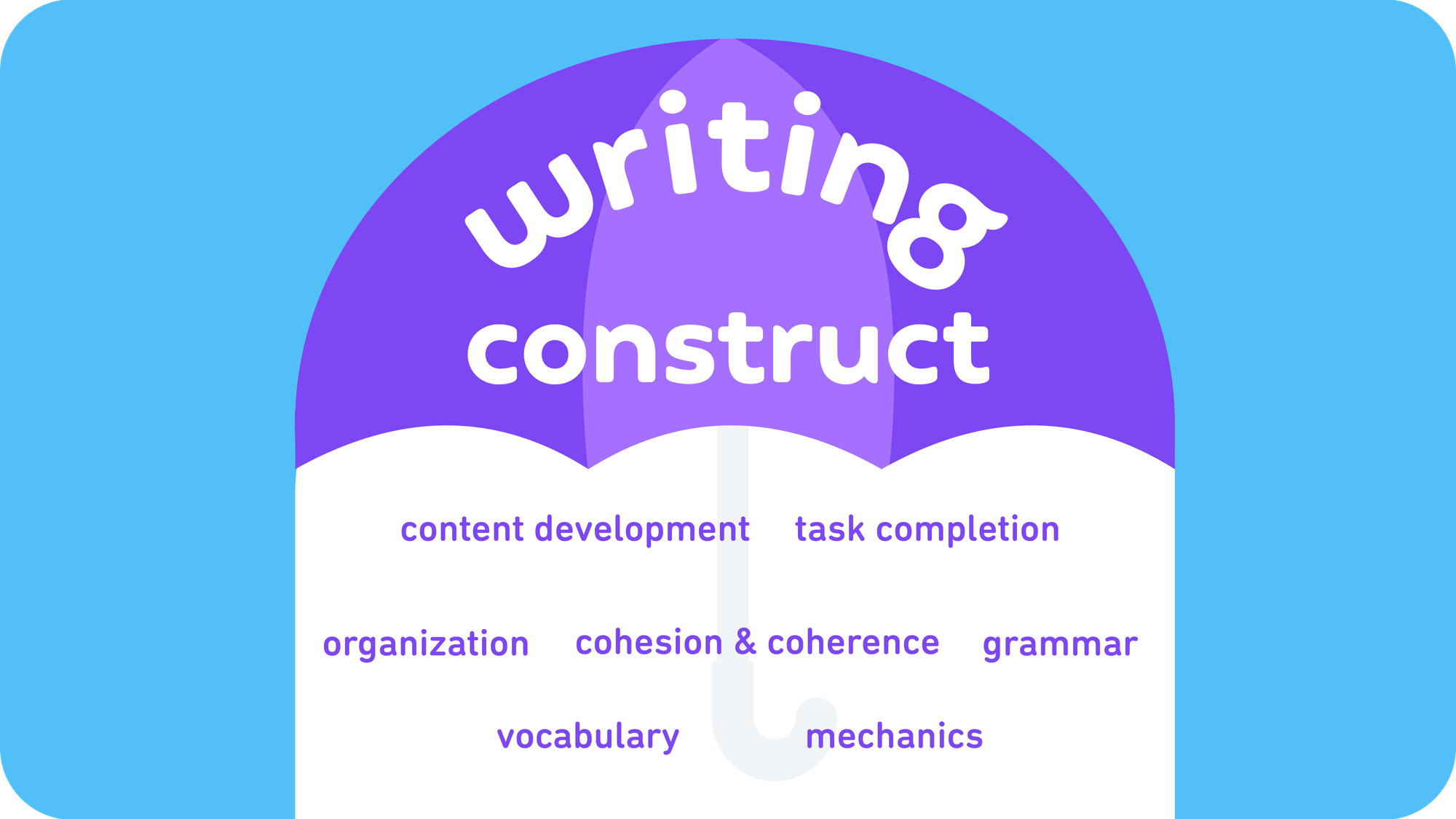

At its core, the writing construct on the DET captures these dimensions through several sub-constructs, such as the ability to:

- generate content and ideas that achieve task requirements,

- organize information with clarity and logical cohesion,

- apply grammatical structures accurately and with appropriate range,

- utilize sophisticated and diverse vocabulary with proper word formation

- demonstrate control of mechanics including spelling and punctuation.

Beyond these textual features, the DET writing construct also reflects the underlying cognitive processes that produce effective writing. Some of these include planning and organization of thoughts, thoughtful revision and elaboration, and careful editing.

Why multiple short tasks beat one long essay

Because the nature of writing is so complex, the DET employs a multi-dimensional approach to evaluating writing abilities. Rather than relying solely on an extended essay format, which has traditionally dominated language testing, the DET incorporates varied task types that collectively assess writing proficiency across different contexts and aspects of the writing construct relevant to university-level English use.

Our approach acknowledges the simple reality: academic writing in university settings has evolved beyond traditional essay formats. By sampling writing across multiple contexts and communicative purposes of the DET tasks, we can gain a more accurate picture of applicants' adaptability to various writing demands.

For example, the written summarization part of Interactive Listening represents a substantial advancement in integrated skills assessment. Research has consistently shown that academic success depends heavily on students' ability to accurately transform information they hear (e.g., lectures, discussions) into written form (Özdemir, 2018). By simulating a conversation that must be summarized in writing, this task evaluates a crucial academic skill that traditional essay-based tasks often miss.

Perhaps most innovative is our most recent addition to the DET writing tasks, Interactive Writing. By requiring test takers to expand on unaddressed themes in their initial response, this task simulates the iterative nature of academic writing, where drafting, feedback, and revision form an essential cycle (Ferris, 2011).

How do we know that the DET approach works?

One of the biggest criticisms I hear about the DET is "but the writing tasks are too short!"

But let’s be honest: how often do students write 50 or 60-minute essays in real life? Almost never. They do, however, constantly write summaries, lab reports, discussion posts, and project proposals, often over the course of several days.

Research on writing assessment validity has also suggested that predictive power increases when multiple samples of writing are collected across varied contexts (Bouwer et al., 2014). Finally, Naismith, Attali, and LaFlair (2024) successfully demonstrated that shorter writing tasks measure writing abilities just as well as longer 20-minute tasks.

Turns out, length isn't everything when it comes to writing assessment.

Masha’s takeaway:

When Hyland (2013) talks about the "evolving ecology of academic writing," he's describing exactly what the DET has captured in its assessment design. University writing isn't just about essays anymore—it's about adapting to different genres, audiences, and purposes. The DET writing construct is rigorous, and reflects exactly that.

And the evidence is clear: shorter integrated tasks are innovative in giving us a clear picture of how students actually write in university settings without making students sit through hours of writing.

💡To learn more about DET construct coverage, explore our research publications!