It started with a simple comment from one of the Duolingo English Test’s UK Advisory Group members:

“We’ve just brought in carbon budgeting for the international office.”Martyn Edwards, while Director of Marketing & Advancement at Loughborough University

That shift in thinking—applying environmental accountability to the admissions pipeline—stuck with us.

Universities already track emissions from buildings, business travel, and energy use. But the norm is to start ‘counting’ from the point of enrolment. Very few have looked upstream at the carbon costs baked into the admissions process itself.

In particular, there has been very little consideration at the university level for the emissions generated when international students travel to prove their English. These are classic Scope 3 emissions, indirect but real.

We’d already begun exploring the travel burden of English testing, mapping test taker locations to nearby SELT centres and asking how far students were having to travel just to prove their English. But we wanted to go further: to explore the social value questions our travel data raised. That’s what prompted us to quantify the carbon impact of switching from traditional in-person English tests to digital alternatives like the Duolingo English Test (DET).

Inspired by the Climate Action Network for International Education (CANIE), we turned to the International Education Sustainability Group (IESG), drawing on their Climate Action Barometer expertise, to commission a study with one goal: to help start a conversation, both in the sector and on university campuses, about the climate impact of institutions’ English language requirements.

The findings are striking, if not surprising.

In-person tests generate far more carbon than digital ones

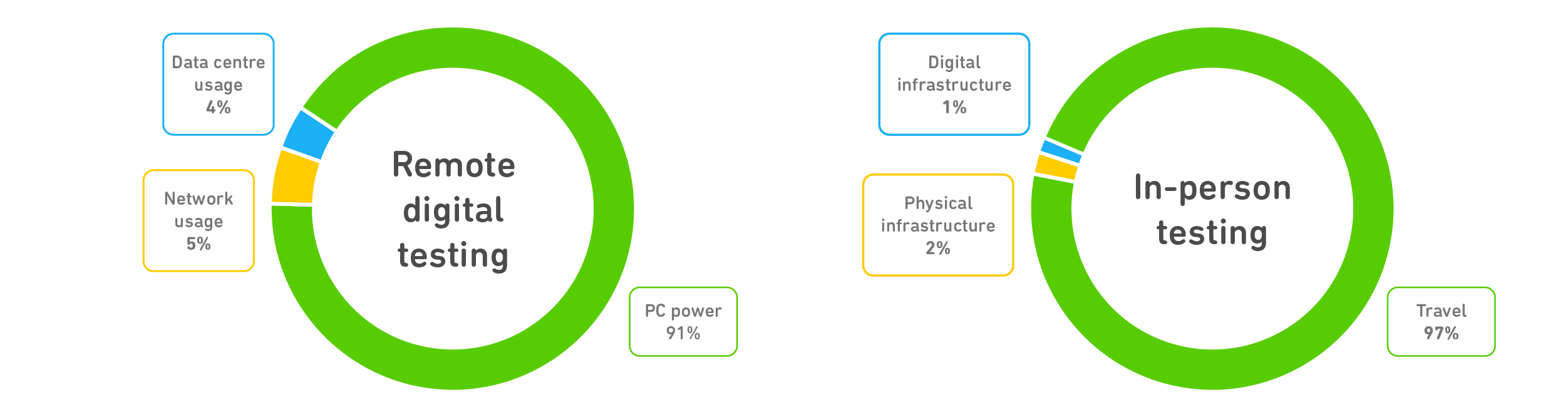

Traditional, in-person English tests generate an average of 14.3 kg of CO₂e per test. That’s mainly due to travel: students frequently make round trip journeys of 175 km, sometimes much farther.

By contrast, a remote test like the DET produces just 0.16 kg of CO₂e, a potential 98% reduction. Put another way, this is the equivalent to the UK sector planting a new Sherwood Forest every year.

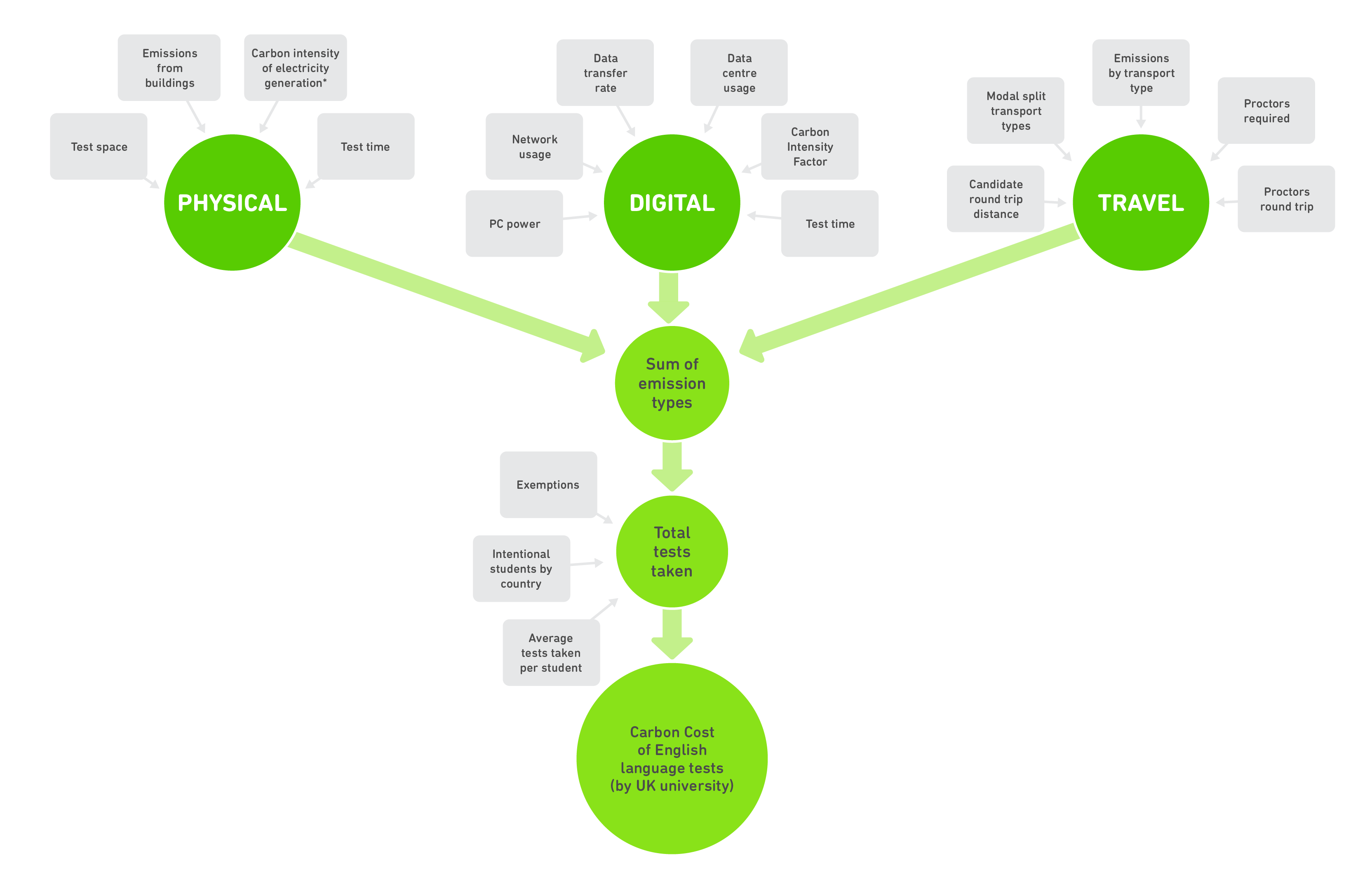

Our framework compares traditional and digital English language tests

This study isn’t a formal carbon audit—it’s an indicative estimate, based on a mix of the best publicly available data and sector-informed assumptions.

The IESG used DET data, carbon intensity by country, and the distribution of SELT test centres; they combined HESA enrolment data with Enroly insights on how students meet English requirements—whether by test, diploma, or EMI waiver—all to model the comparative carbon cost of in-person versus online testing.

For digital emissions, Duolingo consulted its cloud and AI providers, working directly with Amazon’s and Google’s sustainability teams to make DET among the first products to quantify in detail its AI carbon footprint.

Where precise data wasn’t available, IESG took a cautious, conservative approach. But this analysis is, above all, a conversation starter about the carbon implications of international admissions.

Our model calculates three main carbon contributors: test provider emissions (physical and digital); and test taker emissions, whether that means travel to a centre or powering a laptop.

The carbon might not be where you think it is

For both in-person and digital formats, we were struck by how much the carbon footprint of a test came down to just one or two key drivers. The carbon impact of AI and physical infrastructure was modest compared to the power consumption of a student’s computer or the emissions from travelling to a test centre.

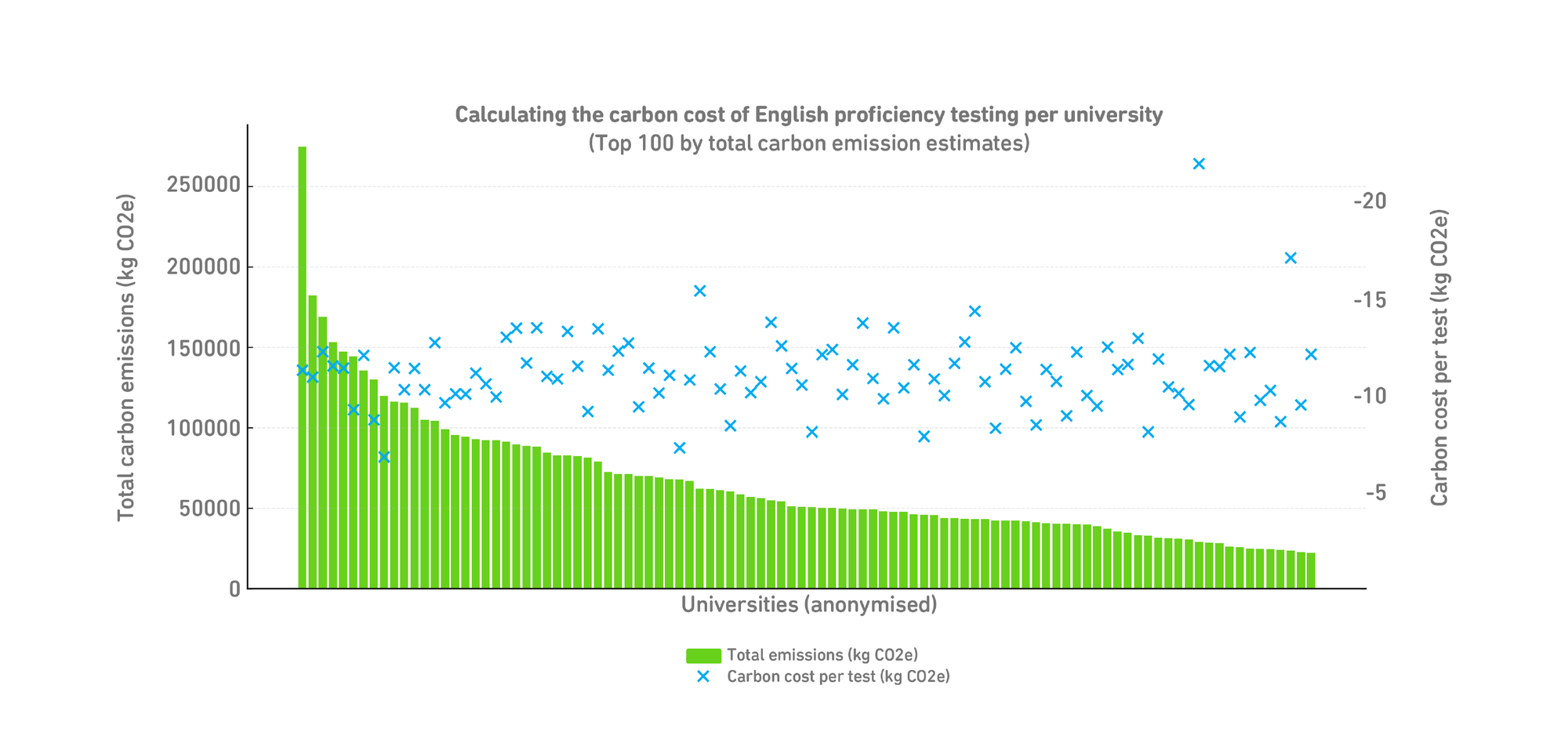

Not all universities carry the same footprint

The calculator IESG developed used a bottom up estimate, drawing on each university’s contribution to the national picture. While there’s an obvious connection to the size of the international student population and total carbon emissions generated, one of the more eye-opening findings was how much the carbon cost per test varies by institution, depending on the make-up of their international student intake.

Switching to secure online English testing may be one of the more straightforward ways for universities to reduce emissions and improve access—without compromising academic standards or compliance.

Beyond carbon: What else do these journeys tell us?

While this report focuses on emissions, the travel data raises broader questions about access and equity. What is the burden on applicants from fragile or remote contexts? What happens in places with unreliable electricity or regular internet blackouts? What barriers exist for students with limited mobility, resources, or connectivity?

These are equally important questions, and we hope they will continue to shape sector conversations alongside sustainability.

We hope this analysis encourages more institutions to explore the impact of their admissions processes and consider practical, inclusive alternatives.

📩 To see the data for your university, get in touch at institutional@duolingo.com or hello@iesg.eco